Globally, the outlook for auto sales is similarly uneven, so much so that the future of some of the biggest players is open to debate. All eyes are on the US automakers General Motors, Ford Motor, and the Chrysler unit of DaimlerChrysler. GM and Ford are in the early stages of crucial multiyear turnaround plans, especially in their key North American markets, and Daimler appears intent on spinning off Chrysler rather than pursuing the synergistic strategy that led it to buy the U.S. car company in 1998. However, Detroit doesn't have a monopoly on problems. In Europe, for instance, both Peugeot S.A. and Renault S.A. face their own struggles to preserve market share and shore up profitability.

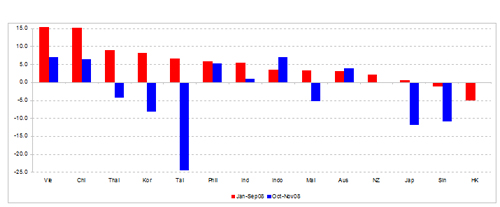

Overall, Standard & Poor's Ratings Services sees vehicle sales pretty much flat in the US and Europe, with the best hope for strong growth in Asia (see Chart 1). In the US, lower gasoline prices will likely offset higher interest rates in a slowing economy, with the net result of keeping unit volume just slightly below last year's 16.5 million vehicles. In Europe, the UK and Spanish markets will continue to see slight declines, while Germany and France could see some upside. However, further tightening by the European Central Bank should help slow down consumer durable sales.

That leaves Asia, with its booming Chinese and Indian economies, as the exception to this global rule. Demand for automobiles in emerging Asia is potentially large, with growth at an average annualised 7%. In addition, the region's expanding middle class is creating new demand for cars, helping to offset the slowdown in Japan and elsewhere.

Tough Road Ahead For The U.S. Auto Market

In recent months, US automobile sales have held up well, even for US manufacturers. However, the unexpectedly upbeat sales performance was more likely a short reprieve from what will likely be a sluggish year for the U.S. auto market.

US macroeconomic outlook

A nation's auto demand depends on the strength of its economy, so as long as the U.S. is doing well, people will be all-too-willing to buy new cars. Now in its sixth year of expansion, however, the U.S. economy is slowing, with annualized real GDP growth of just 2.2% in the fourth quarter of 2006. For 2007, we expect that real GDP growth will come in at a slower 2.4% but will still be enough to generate solid income gains. That lower rate, however, provides little cushion if oil prices spike or the housing and stock markets unravel more than expected. Nevertheless, except for housing, the economy has held up surprisingly well.

Despite the economic slowdown, consumer spending remains resilient, rising 4.2% in the fourth quarter of 2006, but first-quarter 2007 sales suggest some loss of steam. With employment and income growth healthy and stock-market gains helping to offset housing weakness, Americans can still pony up the money for a new car. The drop in the unemployment rate back to 4.5% in February and recent sharp upward revisions to payrolls strengthened household incomes. Moreover, the energy-related drop in inflation helped push real earnings into positive territory (up 1.5% over the last 12 months) to boost spending.

American consumers continue to live beyond their means. The saving rate was negative 1.2% in the fourth quarter of 2006 and averaged negative 1.1% for the year, the lowest since the Depression. For the first time since 1932-1933, the saving rate has now been negative for two consecutive years. Although the pace of borrowing has decelerated, average household debt hit yet another record: 137% of after-tax income in the fourth quarter of 2006. That burden will be a drag on future spending.

But spending more than they earn does not seem to bother most Americans, in part because household wealth is doing well. Most people measure savings by what they have in the bank today versus a year ago. By that standard, Americans are getting wealthier. The stock market recovery and higher home

prices boosted net worth last year. The ratio of net worth to income hit 575% at the end of 2006, not quite at its peak of 615% reached seven years earlier but a record for any time before 1997.

Low interest rates and strong house prices encouraged homeowners to tap their home equity for money to spend. Freddie Mac estimates that homeowners took more than $626 billion out of their homes' equity in 2006. Based on Federal Reserve survey data, we estimate that nearly half that money went into

consumption (including education). Now, however, higher interest rates and weaker home prices make this option less attractive. We expect home prices to fall 9% from their mid-2006 peak, damaging wealth and slowing growth in borrowing and spending but leading to a higher saving rate in 2008.

The authors of this article are:

David Wyss, Chief Economist, Standard & Poor's

Beth Ann Bovino, Senior Economist, Standard & Poor's

Jean-Michel Six, Chief European Economist, Standard & Poor's

Risks for the U.S. car market

Given this economic backdrop, Standard & Poor's expects motor vehicle sales to be flat this year, as somewhat lower gasoline prices offset higher interest rates. Sales incentives helped soften the impact of higher gasoline prices on car sales last year, but recent data suggest that discount programs have lost

steam. Sales of light vehicles were 16.5 million in 2006, down from 16.9 million in 2005. Standard & Poor's expects them to edge down to 16.4 million in 2007.

Higher interest rates and oil prices are two big negative factors when considering whether to buy another car, particularly when household debt is at record levels. Rising interest ratesùtogether with slowing U.S. growthùare increasing the strain on consumers. The Federal Reserve hiked short-term rates 17 consecutive times, but long-term interest rates have remained steady at low levels. That's keeping debt-service costs reasonable despite being at a record high. Although most Americans are still keeping up with their monthly payments, recent delinquency reports indicate signs of weakness. Those who

manage to meet their obligations might think twice before adding to their debts.

Higher oil prices could cause consumers to not only reconsider whether to buy another car but also what kind. With oil still down from August's record highs, lower gasoline prices at the pump will convince some consumers, particularly lower income ones, to buy another car. We expect oil prices to hold near $60/barrel this year, which will support spending.

On the other hand, oil prices spiking above $100/barrel or a pullback of foreign investment into the U.S. could derail growth. An overly tight Federal Reserve policy, together with a rebound in oil prices, could send the economy into a recession in 2007. And if the housing adjustment occurs suddenly, troubles will be much worse. Given our current forecast of only 2.4% GDP growth in 2007, that could push the economy perilously close to recession.

How European Economies Are Shaping Up Moving somewhat in the opposite direction of the U.S., the Eurozone economy surged in 2006 after several years of sluggish growth. Compared with a 1.5% expansion in 2005, GDP growth reached 2.6% in 2006. A sharp rebound in investment and exports was the primary driver of that surge, however, and consumer demand remained rather subdued. European firms' profitability continued to improve because of effective cost controls, particularly a firm grip on wage increases. In turn, consumer income growth

stayed sluggish, and the modest increase in overall consumer demand (1.9% in 2006 versus 1.4% a year earlier) was mainly financed through credit on the backdrop of low interest rates.

The outlook for 2007 and beyond remains positive, though tighter fiscal policies in Germany (a 3% increase in VAT rate in January 2007) and Italyùcombined with higher interest ates as the European Central Bank carries on tighteningùshould lead to a temporary slowdown. We project GDP growth to

reach 2% this year. Consumers should benefit from lower unemployment across the region, but real income growth should not accelerate significantly from 2006. Overall, we expect consumer demand to grow 2% in both 2007 and 2008.

Meanwhile, the U.K. economy should continue to grow at a solid clip: 2.6% this year (the same as in 2006) as investment andùto a lesser extentùconsumption continue to rise. Unemployment will likely stay fairly stable (3.1%). The Bank of England remains concerned that stronger growth and low unemployment could eventually result in higher inflation, and after the 25-basis point hike to 5.25% implemented last January, we think the bank will raise its rate once more to 5.5% before the summer.

This further tightening should hit consumers, causing a slowdown in housing markets and in consumer durable sales.

Where Europe's Auto Market Appears To Be Heading

In 2006, Western European (the European Union and Switzerland) car sales were broadly flat (plus 0.7%) compared with the previous year but with markets running at very differing rates. The U.K. and Spanish auto markets eased, while Italy's and Germany's strengthened. Growth in sales at new EU member states was higher, at 2.2% year over year.

As in the U.S., sales incentives are a big factor. Manufacturers have been increasingly using them to stabilize what would have otherwise been more cyclical market swings, a trend we expect to continue unabated as competition remains intense. Asian players should gain market share in Europe and will

likely add capacity, notably in the east, with limited western adjustments.

For 2007, we look for another flat year in terms of volume. However, there is a tougher outlook in the first part of the year on demand payback (notably in Germany) and a difficult comparison base. Strength will appear later in the year as consumer spending improvements support overall demand upticks. Italy should also see strong support from its scrappage incentive. In summary, we see the U.K. and Spanish markets continuing to decline slightly, with prospects for upside in Germany and France marginal at best. In 2008, there should be a further year of marginal growth, held back by some payback distortion in Italy, though a more solid German and French market recovery should be filtering through.Germany

The German car market was solid in 2006, up 3.8%, with fourth-quarter sales gaining 12.1% year on year because of the then-imminent VAT hike. This should be followed by the inevitable demand payback. Indeed, sales are already down 10%-15% year-over-year through January and February 2007. This should be difficult to compensate for during the remainder of the year, resulting in a slight market contraction despite a progressive pickup in the economy overall. Nevertheless, replacement demand should provide some underlying support to the market as the parc age continues to tick upwards. We look for a solid 2%-3% market recovery in 2008/2009.

France

The French car market was highly volatile through 2006, falling 3.3%. The level of decline was somewhat surprising given the improvement in consumer spending and confidence, as unemployment had been falling throughout the year. New model activity has proved much less of an attraction than in previous

cycles, and the financial weakness of domestic players has limited incentive spending to support the market. Although we do not expect a sharp upturn in sales through 2007, we believe that the trough has been reached and look for some market stabilization this year. Any rebound, however, would be tempered by the expected continued financial weakness and possible restructuring of domestic players.

U.K.

The U.K. car market continues to be weak, falling by 3.9% in 2006, the third year of decline. Through 2007, we expect the market to continue to make small downward moves, falling about 1%-2%, though the decline will be less than in 2006, given the impact of higher rates on consumer spending and confidence.

Any notable slowdown in house prices would be a pronounced risk to that forecast. In 2008, there should also be relatively anemic growth before replacement demand supports a more solid uptick in 2009.

Spain

The Spanish car market has been taking a breather of late from its recent strong growth path, falling 2% in 2006 but remaining relatively healthy as it matures. In line with the moderation in consumer spending and unemployment stabilization, we expect the Spanish car market to slip in 2007 to 1.5 million sales compared with 1.61 million in 2006.

Italy

The Italian car market was solid through 2006, gaining 1.4% year on year, with improving consumer confidence despite some shakiness in unemployment levels. Solid consumer spending should broadly continue through 2007, though the car market growth itself should be mainly underpinned by the scrappage incentive renewal, which should add some 100,000 units to 2007 demand. The local auto

association, Anfia, is forecasting 8%-9% growth. An inevitable demand payback should follow in 2008 in our view, weighing what should otherwise be a more solid uptick relative to the overall western European car market.

Booming Economies Spur Auto Sales In Asia

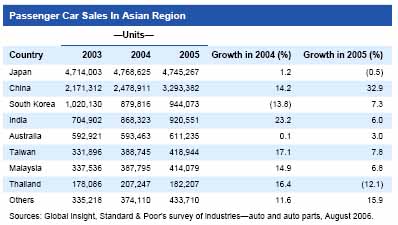

Asia now has four of the 15 largest auto markets in the world. It accounted for about 27% of new passenger car registrations worldwide in 2005 (according to Global Insight data). As emerging Asian markets grow by more than 7% annually on average, the potential increased demand for automobiles is enormous. Rapidly rising per capita incomes, low vehicle penetration, increasing rates of car replacements, and more orders for premium and fuel-efficient cars in these economies are driving the demand. China and India have become the obvious target markets, with dramatic jumps in passenger car demand.

Although Japan remains the region's largest auto market, sales have nearly peaked, as the youth demographic, which has a high propensity to purchase automobiles, is declining.

Demand for passenger cars generally moves in tandem with GDP growth, rising during periods of economic expansion and falling during periods of economic contraction. In Japan, however, automobile sales have not kept pace with the recovering growth. On the contrary, new car sales actually declined 0.5% to 4.75 million vehicles in 2005 and dropped a further 1.5% year-over-year in the first five months of 2006, according to Global Insight data.

But China and India are more than offsetting the slowing demand in Japan. China's and India's collective sales were only 531,000 short in 2005. From 2002 to 2005, annual passenger car sales increased about 151% in China and nearly 53.4% in India. Over this period, per capita income in China and India has risen at compound annual rates of 12.4% and 9.8%, respectively. More important, the burgeoning middle class in these economies has created a new demand for passenger cars.

Although both China's and India's auto markets are booming, the two have several differences. Chinese car sales are nearly four times India's, despite a fragmented industry structure and low finance penetration, which could have slowed growth in Chinese car demand. Moreover, although small cars have dominated Indian roads for some time, in China, ownership is only recently shifting from government (or institutional) to private consumers, translating into higher demand for small cars. Hence, the Chinese car market is likely to sustain higher growth levels than the Indian car market over the next few years

(CRIS Infac Report: Cars and Utility Vehicles December 2006).

However, auto sales in the region remain vulnerable to high oil prices, which peaked at $78/barrel in August 2006. The oil market continues to be tight and susceptible to geopolitical risks. In addition to higher consumer purchasing power, the desire for fuel-efficient cars and national environmental pollution

policies have become significant determinants of demand. For instance, in April 2006, the Chinese government introduced a consumption tax that favors smaller and more fuel-efficient vehicles. In Japan as well, the growth trend in the mini-vehicle market (small, energy-efficient, low-priced cars) is stronger than for other kinds of automobiles.

Overall, sustained economic growth reinforced by rising rates of urbanization and employment and widening access to finance in the region will continue to bolster demand for automobiles in 2007.

Main References:

Survey of Industries: Auto and Auto Parts û Asia, August 2006.

CRIS Infac: Cars and Utility Vehicles, December 2006.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.